Drug-induced psychosis is a syndrome of psychotic symptoms, such as delusions and hallucinations, resulting from substance use or withdrawal. While symptoms may be similar to other disorders with psychotic features, they vary depending on the substance, dosage, frequency of use, and co-occurring conditions.

Mental health help for substance use disorder Get help from a real doctor who takes insurance. Talkiatry offers medication management and supportive therapy in online visits with expert psychiatrists. Talkiatry believes that treating anxiety, depression, and other mental health conditions that commonly lead to or coexist with substance use disorders is a critical part of treating SUD. Take the online assessment and have your first appointment in days. Free assessment.

What Is Psychosis?

Psychosis is characterized by a disconnect from reality, possibly caused by preexisting medical or psychiatric conditions, external substances, and trauma. Symptoms can be observed in several personality, mood, or psychotic disorders (e.g., schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, schizotypal personality disorder, etc.). In other cases, psychosis may occur due to a neurological condition, such as Huntinigton’s or a brain tumor. Exhibition of symptoms will vary depending on the cause of the psychosis, but episodes will typically include similar symptoms.

Symptoms of psychosis include:

- Delusions: Delusions are distorted beliefs that, despite possibly having a kernel of truth, are not supported by the overwhelming evidence accessible to most other objective, non-psychotic observers.

- Hallucinations: Hallucinations are sensory experiences that can take the form of seeing, hearing, or tasting things that aren’t really there.

- Disorganized speech: Disorganized speech does not make logical sense or is incoherent. It may also be the repetition of a word or phrase.

- Disorganized behavior: Any behavior that does not fit a given situation may be considered disorganized.

- Negative symptoms: Negative symptoms refer to the absence of typical features that most individuals regularly exhibit.

What Is Drug-Induced Psychosis?

Drug-induced psychosis may occur after ingesting certain substances, producing symptoms similar to those in formal psychotic disorders. Different substances can induce a psychomimetic (i.e., “mimicking psychosis”) response, and it is estimated that 7-25% of individuals presenting with acute psychotic symptoms for the first time are experiencing this condition.1

Diagnostically, psychotic symptoms present during drug use are classified as “intoxication,” while “drug-induced psychosis” is reserved for symptoms persisting for days or weeks after detoxification.1 Sometimes, drug-induced psychosis converts to a chronic, lifelong primary psychotic disorder. Substance-induced psychotic disorder is classified in the DSM-5 under schizophrenia spectrum disorders, and it can be challenging, even for clinicians, to differentiate symptoms from primary psychotic disorders.

Below are the distinguishing factors of drug-induced psychosis:

- Age: While the age of onset for certain primary psychotic disorders, like schizophrenia, is typically from the late teens to early 30s, many cases of substance-induced psychosis occur outside that age range.

- Family history: A stronger genetic/heritability link is associated with primary psychotic disorders than substance-induced psychosis.

- Symptoms: Substance-induced psychosis produces fewer positive and negative symptoms but more affective and anxiety-related symptoms than primary psychotic disorders.

- Duration: Substance-induced psychosis is relatively brief, lasting from days to weeks. Primary psychoses are often lifelong diseases with acute episodes alternating with periods of remission.2

- Good premorbid functioning: Before the onset of psychosis, individuals with substance-induced psychosis generally don’t exhibit thought disorder or behavioral disturbances, as is sometimes seen before acute episodes of schizophrenia.

How Long Does Drug-Induced Psychosis Last?

Drug-induced psychosis symptoms may start during intoxication and last beyond the elimination of the substance from the body. The duration of intoxication and subsequent drug-induced psychosis depends on the substance type, dose, individual tolerance, comorbidity, and other factors. Some drugs may cause long-term changes to brain pathways, in which psychotic symptoms may persist for longer.

How Does Drug Use Cause Psychosis?

Most drugs that cause psychosis work by altering neurotransmitters in the brain. Neurotransmitters work together, not in isolation, and changes to one will usually affect others. Dopamine and glutamate changes in the prefrontal cortex and midbrain may be responsible for many psychotic effects. One exception is that psychedelics (e.g., LSD, psilocybin, MDMA/”ecstasy”) typically modulate serotonin (5-HT) in these regions to produce mind-altering effects.

Different neurotransmitter mechanisms cause various clusters of psychotic symptoms. For example, stimulants and THC often evoke paranoia, LSD elicits visual hallucinations, and amphetamines or cocaine yield persecutory delusions and hallucinations of bugs crawling on oneself. Furthermore, some drugs, like methamphetamines and cocaine, engage the brain’s reward circuit more than others and are thus more addictive–leading to heavier use and prolonged psychotic symptoms.

Help For Addiction Ria Health: Effective, Evidence-Based Alcohol Treatment 100% Online Quickly change your relationship to alcohol with our at-home program. On average, Ria Health members reduce their BAC levels by 50% in 3 months in the program. Services are covered by many major health plans. Visit Ria Health Workit Health – Online Treatment for Opioids or Alcohol, Including Medication. Modern, personalized recovery that combines medication, a supportive community, and helpful content. Covered by many insurance plans. Currently available in FL, TX, OH, MI, and NJ. Visit Workit Health Best Drug Addiction Rehab Centers – Find the best local detox or drug rehab center covered by your health insurance. Search by location, condition, insurance, and more. Read reviews. Start Your Search

Symptoms of Drug-Induced Psychosis

Drug-induced psychotic symptoms will vary depending on the drug and its associated neurotransmitters. Delusions and hallucinations must be present to receive a diagnosis of substance-induced psychosis, but other positive, negative, and cognitive symptoms common to primary psychotic disorders may also appear.1

Common symptoms of drug-induced psychosis include:

- Hallucinations: Hallucinations are perceptions of things that do not exist. Many hallucinogenic drugs may cause perceptual distortions but not necessarily true hallucinations. Depending on the drug and individual, hallucinations may be visual, tactile, or auditory.

- Delusions: Delusions are beliefs that have little or no basis in reality. Persecutory delusions–that one is being followed or targeted–are the most common type found with drug-induced psychosis, especially for amphetamines, cocaine, and cannabis.

- Paranoia: Related to delusions, feelings of suspiciousness are relatively common in a drug-induced psychotic episode for cannabinoids and stimulants.

- Panic attacks: Extreme anxiety may lead to feelings of panic, especially when hallucinations or delusions are unpleasant. The content of hallucinations and delusions induced by various psychotropic drugs is often unpredictable.

- Agitation: A state of irritability and restlessness is a common symptom of drug withdrawal but can also be present beyond acute withdrawal as part of a drug-induced psychotic state.

- Disorganized thinking: Cognitive impairments such as illogical thinking may accompany hallucinations and delusions.

- Disorganized behavior: Inappropriate behavior may occur due to hallucinations, delusions, or cognitive impairment.

- Lack of insight: This is a fundamental characteristic distinguishing drug intoxication from drug-induced psychosis. During intoxication, the person is usually aware that hallucinations, delusions, or perceptual distortions are due to the substance ingested. However, during a drug-induced psychotic episode (or primary psychotic episode), the individual is unaware of the connection between substance and symptom.

Drug-Induced Psychosis Vs. Drug-Induced Schizophrenia

Certain drugs may cause symptoms that mimic schizophrenia or related psychotic disorders (i.e., they are psychomimetic). Due to this similarity, the terms drug-induced schizophrenia and drug-induced psychosis have been mistakenly used interchangeably. However, they refer to different conditions, with the former term being an outdated misnomer.

The link between schizophrenia and drug use is complex and only partially understood. It’s often challenging for clinicians to differentiate between psychosis caused by a substance versus schizophrenia. Schizophrenia is a primary psychotic disorder caused by factors other than consuming a substance. However, schizophrenia’s onset can be triggered or exacerbated by certain substances, especially in the late teens to early 30s. Indeed, drug-induced psychosis can convert to a primary psychotic disorder, but that can only be determined after at least a month of abstinence from the substance. This conversion of drug-induced psychosis to a primary psychotic or bipolar disorder occurs in 46% of cannabis-induced psychosis, 32.3% of amphetamine-induced psychosis, and 24% of hallucinogen-induced psychosis cases.3

On average, primary psychosis patients have an earlier age of onset than drug-induced psychosis patients, a stronger family history of psychotic disorders, less insight into the cause of symptoms, more positive and negative symptoms, fewer depressive symptoms, and less anxiety.

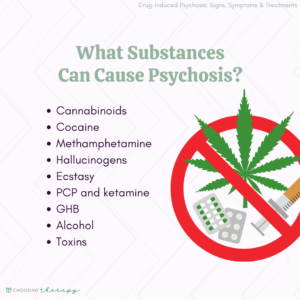

What Drugs Can Cause Psychosis?

The list of substances that can cause psychotic symptoms continually increases as new synthetics enter the market. Drugs that can lead to psychotic symptoms include stimulants, cannabinoids, psychedelics, and cathinone. The amount of each substance that would induce psychotic symptoms may be affected by metabolic rate and amount ingested, other medications, and comorbidities.

Substances that may cause psychosis include:

Cannabinoids

THC is the active ingredient in marijuana that can cause psychotic symptoms, such as delusions, hallucinations, and disorganized thinking or behavior. Though psychomimetic effects are temporary for most, psychotic symptoms occur in approximately 15%-50% of cannabinoid users.5,7,8

Cocaine

Cocaine can also induce psychotic symptoms, especially with repeated administrations (i.e., binging) and higher doses. Younger users are more likely to experience psychotic symptoms. Estimates of cocaine use leading to substance-induced psychotic disorder vary in literature from 6%-40.5%.5,7

The most common psychotic symptoms reported with cocaine use are paranoid delusions (90% of users experiencing psychotic symptoms) and hallucinations (96% of users experiencing psychotic symptoms). Hallucinations are commonly auditory but can also be visual, and paranoia manifests as suspiciousness and irrational distrust of others.5,7

Methamphetamine

Methamphetamine (a.k.a., “Meth”) is a highly addictive stimulant that can lead to substance-induced psychosis in 17-43% of users.10 The most common symptoms reported include persecutory delusions (occurring in 84% of individuals with psychotic symptoms), auditory and visual hallucinations (69% and 65%, respectively), hostility (5,3%), and conceptual disorganization (36%).

Methamphetamine increases dopamine and glutamate in the ‘reward’ (mesocorticolimbic) circuitry. These drugs can damage the cortex and dysregulate glutamate pathways connecting the thalamus and cortex, which might contribute to psychotic symptoms.

Hallucinogens

Hallucinogens (a.k.a., psychedelics) are categorized into classic and dissociative classes.6 Hallucinogens can be addictive, but most drugs in this class do not lead to drug-induced psychosis.6 Only 20.9% of LSD users and 18.8% of psilocybin users convert to experiencing true hallucinations or delusions.7

While intoxicated, users may experience perceptual distortions involving time, shape, color, movement, size, and even a blending of senses (i.e., synesthesia), like hearing color or seeing sounds. True hallucinations are not as common as perceptual distortions when the user is often aware that the altered state of mind is due to the substance.

Ecstasy

Ecstasy is a synthetic amphetamine that shares properties with both stimulants and hallucinogens and works by increasing serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine. Primarily a mood enhancer, ecstasy can elicit energy, euphoria, and intense love for oneself or others. Though distorted perceptions may occur with acute use, few psychotic symptoms are reported during intoxication (4.3%).7 However, when used chronically, this drug can cause long-term neurotoxicity (i.e., lasting changes to serotonin levels), and persistent psychotic symptoms may ensue, such as delusions of grandeur, paranoia, visual hallucinations, and conceptual or behavioral disorganization.11

PCP and Ketamine

Among a small percentage of users, PCP and ketamine can cause positive, negative, and cognitive symptoms typical to psychosis, even after the drug is eliminated from the body. Psychomimetic symptoms may depend on the heaviness of use but include hallucinations, delusions, disturbed emotion and affect, and decreased motivation. Persistent psychotic symptoms triggered by PCP can last for days or up to six weeks, while psychotic symptoms resulting from ketamine use are milder and short-lived.12,13

It is estimated that ketamine induces psychomimetic symptoms in a relatively low percentage of users (3.9%). While estimates of psychosis are not available for PCP usage, it is more potent than ketamine in eliciting psychotic symptoms and is thus no longer used in medicine.7

GHB

Chronic use of gamma-hydroxybutyric acid (GHB) can lead to negative symptoms like those seen in primary psychotic disorders, such as apathy, alogia, anhedonia, and asociality. However, positive psychomimetic symptoms may arise during withdrawal from GHB in a relatively low percentage of individuals (1.9-3.5%) and include hallucinations, delusions, disorganized speech and behavior, and agitation.7,14 When these symptoms last beyond acute withdrawal, GHB-induced psychosis may be designated.

Alcohol

An estimated 0.4-7% of individuals with alcohol dependence will experience alcohol-induced psychotic disorder.15,16 Also referred to as alcohol hallucinosis, psychomimetic symptoms can include hallucinations and delusions.16 Symptoms may reduce over time with abstinence but can become chronic in 10-20% of people with alcohol-induced psychosis, lasting upwards of 6 months. Alcohol hallucinosis is a condition distinct from the acute ethanol withdrawal state, delirium tremens. The neurophysiology of alcohol hallucinosis is not fully understood but is thought to be related to glutamate-mediated NMDA receptors, dopamine, and GABA.

Toxins

Certain elements in one’s environment–such as lead, gasoline, glue, paint thinners, organophosphate insecticides, nerve gas, and anticholinesterase–have been shown to cause psychotic symptoms. However, the prevalence of toxin-induced psychosis is not clear.1,17,18,19

Treatment for Drug-Induced Psychosis

The first step in treating substance-induced psychosis is to remove the offending substance from one’s system. This is usually best accomplished in a medical setting with support staff to help avoid harm to the individual or surroundings. In many cases, treatment may involve abstinence. In other cases, medications to help the elimination process or to counteract the effects of the offending agent might be administered. 18 When removal of the offending substance leads to withdrawal symptoms, stabilization drugs may be given and gradually reduced to ease the individual through withdrawal.

Mental health help for substance use disorder Get help from a real doctor who takes insurance. Talkiatry offers medication management and supportive therapy in online visits with expert psychiatrists. Talkiatry believes that treating anxiety, depression, and other mental health conditions that commonly lead to or coexist with substance use disorders is a critical part of treating SUD. Take the online assessment and have your first appointment in days. Free assessment.

Although withdrawal from certain addictive drugs (e.g., alcohol, heroin) can give rise to psychotic symptoms, drug-induced psychosis refers to the symptoms persisting after acute withdrawal. For psychotic symptoms extending beyond a month, a clinician will distinguish whether the condition has converted to a primary psychotic disorder (for which a long-term treatment plan would have to be established) or needs longer to resolve.

Drug-induced psychosis presents two distinct but related issues that may require treatment–substance use and psychosis. Unaddressed symptoms of depression and anxiety may contribute to drug misuse and drug-induced psychosis, so an integrated approach is most effective.

Treatment for drug-induced psychosis and comorbid conditions may include:

- Abstinence: Abstaining from further substance use is important for optimal intervention.

- Medication management: After an individual is stabilized, they should be evaluated for any medications that might help treat underlying conditions that led to drug use.

- 12-step programs: Programs like Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) and Narcotics Anonymous (AA) involve flexible but regular attendance to group meetings, adherence to the twelve steps, and usually working with a sponsor or elder in the program.

- Psychosocial training: Social Skills Training (SST) can help individuals develop skills often deficient in those with psychosis and drug dependence. They may involve individual and group work.20

- Psychotherapy: Individual therapy may focus on concrete goals like reality testing of hallucinations and delusions, verbal skills enhancement, maintenance of ADLs, and medication compliance. Insight-oriented therapy may foster a more abstract understanding of the factors contributing to the substance use that triggers psychotic symptoms.

- Family engagement: Family therapy often focuses on how a family system can better prevent the afflicted individual from undue anxiety, frustration, or confusion. Additionally, family members joining for doctor and therapy appointments can make a big difference in the treatment.21

- Contingency management: This involves reinforcing positive behaviors like abstinence, treatment attendance, and medication adherence with “agreed on, immediate, tangible rewards.”22 It is particularly effective for individuals with a dual diagnosis of a primary psychotic disorder and substance misuse.

Drug-Induced Psychosis Recovery

Recovery from drug-induced psychosis often entails a detailed treatment plan and effective coping skills.

Below are some tips for recovering from drug-induced psychosis:

- Plan ahead: When you are experiencing drug-induced psychosis, the altered state of mind may preclude you from figuring out how to get help. Consider establishing a relapse prevention plan, including identifying someone you can contact if you’re experiencing disturbing symptoms.

- Stress management: Misuse of drugs is commonly a coping mechanism for dealing with stress. Avoiding stressful situations is not always possible, and learning techniques to manage stress is essential.

- Avoid drugs and alcohol: Some individuals are more vulnerable to psychotic symptoms than others due to genetics, comorbidities, or environmental factors. Avoiding the offending substance is ideal. If using the drug is not just recreational but a form of self-medication, consider substituting it with well-researched psychiatric medications tested to ensure purity and potency.

How to Help Someone Experiencing Drug-Induced Psychosis

It can be unsettling to witness someone experiencing drug-induced psychosis. It is generally recommended to stay calm and avoid agitating the individual. If the person has not already received medical attention, encourage them to get professional help or call 911 if you are unsure if they are at risk for harm to themself or others. As drug-induced psychosis can last for weeks, be patient and supportive to the person as they recover.

You can support a loved one experiencing or recovering from drug-induced psychosis by:

- Seeking medical assistance: Drug-induced psychosis often comes with symptoms that might be difficult to handle at home, putting both the individual and others at risk for harm. Don’t be afraid to call 911 sooner rather than later. Treatments may be available in a clinical setting to help the individual deal with psychotic symptoms.

- Encouraging treatment: While substance-induced psychosis may result from prescribed medicines or toxins, it is more common that this condition results from drug misuse. The person experiencing psychosis may require drug rehabilitation to avoid a recurrence of psychosis or other debilitating consequences of drug misuse.

- Checking-in: If the person lives alone, try to check in on the person frequently or arrange for nursing assistance until the individual is completely recovered. Without being too overbearing, ask the person how they are feeling and try to do more listening than speaking. Try to be a calm, nonjudgmental presence for the person.

- Being patient: It can take weeks for symptoms to resolve. During recovery, individuals may be unable to engage in normal household duties and work activities. Patience and support from family members are critical in giving the individual the time and space to recover.

- Join a support group: A support group can provide a safe, validating environment for individuals to learn tips and strategies. When family members take the time to educate themselves about psychosis, drugs, and how to help their loved one, the individual tends to be more successful in overcoming drug-induced psychosis symptoms and having a successful recovery.21,23

- Self-care: Supporting your family member through persisting psychotic symptoms can be challenging, frustrating, and emotionally exhausting. It is imperative that you take care of yourself as well to recharge, refresh, and de-stress. Take time to engage in self-care to keep yourself strong for others.

Final Thoughts

Drug-induced psychosis can manifest in various ways depending on the offending substance. Symptoms that persist beyond intoxication or acute withdrawal can be frightening for the individual and others. While the condition is relatively brief, it can convert to a primary psychosis or reveal a vulnerability to psychosis. Professional help can often help treat not just drug-induced psychosis but also underlying causes that may have led to drug use in the first place.

To help our readers take the next step in their mental health journey, Choosing Therapy has partnered with leaders in mental health and wellness. Choosing Therapy is compensated for marketing by the companies included below. Online Treatment for Opioids or Alcohol, Including Medication. Workit Health – Modern, personalized recovery that combines medication, a supportive community, and helpful content. Covered by many insurance plans. Currently available in FL, TX, OH, MI, and NJ. Visit Workit Health Alcohol Treatment – Cut Back or Quit Entirely Ria Health – Quickly change your relationship to alcohol with our at-home program. On average, members reduce their BAC levels by 50% in 3 months in the program. Services are covered by many major health plans. Visit Ria Health Drug Addiction Rehab Centers Recovery.com – Find the best local detox or drug rehab center covered by your health insurance. Search by location, condition, insurance, and more. Read reviews. Start Your Search Telehealth Treatment For Opioid Use Disorder Bicycle Health – offers therapy, support, and medication for addiction treatment (MAT). MAT offers the lowest relapse rates for opioid use disorder, helping people to stop using opioids with minimal physical discomfort. Covered by most major insurance. Visit Bicycle Health Drinking Moderation Sunnyside – Want to drink less? Sunnyside helps you ease into mindful drinking at your own pace. Think lifestyle change, not a fad diet. Develop new daily routines, so you maintain your new habits for life. Take a 3 Minute QuizAdditional Resources

Best Online Medication-Assisted Treatment Programs Online medication-assisted treatment programs are fairly new to the telehealth industry, but existing companies are expanding quickly with new programs emerging every day. It’s important to explore your options and understand the level of virtual care available so you can choose the best addiction treatment program for you.

Best Mindful Drinking Apps If you’re thinking about joining the sober curious movement and you’d like to cut back on drinking, mindful drinking apps are a great place to start. Practicing mindful drinking can take some time, attention, and patience, but with the help of the right app, you can completely transform your relationship with alcohol.